Coltrane’s A Love Supreme: Live in Amsterdam reissue from the Branford Marsalis Quartet out now and available on vinyl for the very first time Read more »

Coltrane’s A Love Supreme: Live in Amsterdam reissue from the Branford Marsalis Quartet out now and available on vinyl for the very first time Read more »

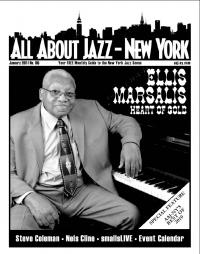

Ellis Marsalis: Heart of Gold

Publication: All About Jazz- New York

Publication: All About Jazz- New York

By: Laurel Gross

Date: January 2011

Ellis Marsalis Jr. has accomplished a lot during his distinguished life in jazz - creating beauty as a firstclass pianist and composer, guiding and inspiring budding musicians through his unswerving devotion as an educator in or near his hometown of New Orleans and with his wife Dolores producing a family of six that includes four high-achievers with notable jazz lives of their own.

Marsalis, who celebrated his 76th birthday this past November, has further reason to celebrate. This month he receives the National Endowment for the Arts’ Jazz Master Award. And in an unprecedented move in the 29-year history of the award, the NEA has chosen to bestow this honor on a family of musicians rather than solely on individuals. So Marsalis’ four musical sons - Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo and Jason - also will receive official Jazz Master status at a ceremony and concert at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater on Jan. 11th. (The $25,000 fellowship part of the award will go to the parent.)

Marsalis has never been one to stand still and he isn’t going to start now. The day before the award ceremony he’ll be participating in a public panel discussion at Jazz at Lincoln Center representing the family and four other 2011 honorees and then swing up Broadway to the Apple Store at 67th Street to give an hour-long performance tied to the release of his An Open Letter to Thelonious in iTunes’ new digital ‘LP’ format (bonus features including video). And Music Redeems, the CD of a live performance the family gave at the John F. Kennedy Center to benefit The Ellis Marsalis Center for Music in New Orleans Musicians’ Village, was released last summer (proceeds go toward construction of that multi-use facility that will include performance, education and recording spaces). With all that the elder Marsalis has accomplished and with everything that’s going on currently, could there be anything he hasn’t gotten around to that he would have liked to do? Anyone he would have liked to play with, whom he didn’t get to play with, for instance? What if he could pick anybody, from any time?

“Well, I remember…,” Marsalis laughs. It’s a nice laugh and, like his playing, it’s fully engaged, totally present. “I remember I told Miles Davis one time, ‘Yeah, man, I always wanted to play with you.’ And he said, ‘You’d better be glad you didn’t because whoever played with me is dead.’” He laughs and there’s nothing half-way or small about it. “Yeah, there was so much to learn playing with Miles you know. I think I would have enjoyed playing with Coltrane too.”

But he did get around to many other things, including his family; they’ve each found their own way to be themselves within the music. You’d probably have to be a resident of another planet devoid of outside communication not to have heard of second son Wynton, who grew up to become a trumpet phenomenon, bandleader and composer and is also Artistic Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, Music Director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and a tireless advocate for the music. It would also be hard not to know about first-born Branford, an impressive and in-demand tenor saxophonist who has an entrepreneurial spirit, heading his own record label, Marsalis Music. Third son Delfeayo has made his mark as a trombonist and as a record producer. Drummer Jason, the youngest in the family, also plays vibraphone. Like their father, all of the Marsalis brothers compose music. (The proud parent says a piece written by Jason, heard on Music Redeems, will be performed at the awards event.)

Juggling performing with a full plate of teaching and then directorships of jazz studies programs at universities, the elder Marsalis has remained an active presence on stages in New Orleans, earning respect as a prominent figure there. Early on he recorded with Cannonball and Nat Adderley (billed as one of the “new stars” of New Orleans for 1962’s In the Bag), played with like-minded modernists whether local or from farther afield (a combo with drummer Ed Blackwell and others got the attention of Ornette Coleman) and there was work with Al Hirt and others.

When asked if anything in particular brought him to jazz, Marsalis recalls, “There was only one radio station in the city that played music at least the first 10 years of my life. And most of it wasn’t jazz. I’m not sure when I first heard it. But now and then I heard Artie Shaw’s group - the Gramercy Five. And I liked that. And they would play Louis Armstrong now and then, not a lot. So I think that by 12 or 13… I was in high school and got to know people in the city who had the same type of interests and put a little band together with some friends. That had a practical side. We figured we could put some money in our pockets. So we just learned and imitated the popular musicians of the day. Which was rhythm and blues, and that music, R&B, is very close to what would become jazz on a more advanced level anyway. But some people went beyond rhythm and blues, some didn’t. I did have one ‘ah-ha’ moment, though it didn’t ‘introduce’ me to it. When I was in high school Dizzy Gillespie came with his band to New Orleans and I got to hear him. And I knew that’s what I want to do.”

Interestingly, Marsalis didn’t start out on the piano nor listening to pianists. “I started out playing clarinet and then saxophone, so I was listening mostly to saxophone. Mostly that was local R&B. There was a tenor player with Fats Domino’s band and another guy I can’t remember his name, he was just called Batman. He was with a group called Roy Brown and his Mighty Men. Eventually when I started to buy records I would listen to recordings that were suggested by friends. And Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt used to come here all the time… By the time I was close to graduation from college I went to a jam session one Sunday and heard a tenor player named Nathaniel Perrilliat and after I heard him, I put the tenor in its case and never took it out again.” So it was time to figure out what to do at that point. “I had studied piano with a teacher but I wasn’t serious. I would just play and doodle around on it. But I had some piano skills so I decided I was going to have to go with that because I wasn’t going to play tenor and clarinet had been gone, because it was played in symphony orchestras or traditional jazz and I didn’t have anybody I knew who was playing traditional jazz and the symphony was out.” Oscar Peterson became an influence.

And for all of his sons’ accomplishments, Marsalis is emphatic that he cannot take credit. He says he was not their first teacher and didn’t push music on them. “It was there for them to become involved in. New Orleans is such a diverse place. They all went to the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts where they were really exposed across the board.”

After conducting an informal but by no means comprehensive survey of nearly a dozen of his recordings, one can’t help wondering what might have happened if Marsalis had moved to New York after getting out of the Marines in 1958. It’s hard not to entertain the thought that he might have greatly increased his chances of becoming more widely known and appreciated (much sooner) as a highly gifted jazz pianist and composer outside his hometown. Hearing his Piano in E/Solo Piano, recorded live during a onenight concert in 1986, a kind of farewell concert on the occasion of his relocating to take up a professorship and directorship at the University of Richmond, putting the period to a 12-year residency at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, you feel you are in the hands of a master. Picking your favorite track of these seven would be like being forced to choose a favorite child - they all have their strengths. Marsalis may not have gotten to New York but the road he did take yielded remarkable results. Not only did he inspire his sons but the list of former students who benefited by his tutelage approaches a Who’s Who of younger players: Terence Blanchard, Nicholas Payton, Harry Connick Jr. and Donald Harrison.

It might have been a bit easier if the young Ellis Marsalis had been able to have the Ellis Marsalis who fostered all those students to guide him. As he sums up, “There were no schools that were particularly going to present things to you in any sequenced order.” But you come across music and people and the experiences build and add up. “But you have to be susceptible to be receiving what is presented. You never know when you first hear something or somebody and it sort of grabs you.”

Categories

Tags in Tags

Branford Marsalis Branford Marsalis Quartet ellis marsalis four mfs playin' tunes Joey Calderazzo Justin Faulkner Marsalis Family marsalis music metamorphosen miguel zenon music redeems new orleansFilter by Artist

Marsalis Music Radio

Join Our Mailing List

- RT @bmarsalis: Compliments of the @T_Blanchard archives. https://t.co/4RsXbyEloa — 1 year 25 weeks ago MarsalisMusic